Most classics have a barrier to surmount before the ‘go’ button is reached. Jane Austen, arguably Hampshire’s lead brand, is not to everyone’s taste. But if you can navigate the semi-colons and the long sentences – not forgetting the beginning when you get to the end – there is a vigour and freshness that makes it all worthwhile.

However some authors, who at one time might have been candidates for the lead brand, have now virtually disappeared from view, even in books of quotations. One of these is Charlotte M. Yonge (1823-1901), though many of her works are now available in short-run editions or on Kindle. The enormous extent of her work is clear from a Kindle collection of 21,574 pages.

In 2023 the Charlotte Yonge Fellowship will be celebrating the bicentenary of her birth. In her lifetime she was a household name. She wrote more than 200 works of fiction and non-fiction, including at least 40 novels, and published a huge number of articles, but today she is scarcely read outside the world of literary criticism and female studies.

Charlotte was born in Otterbourne, near Winchester, and lived her entire life there, first on her parents’ small estate and later in a house called Elderfield, which still stands. Her father, an Army officer, who had fought at Waterloo, was forced to give up his commission in order to marry her mother. He was ‘an earnest churchman and magistrate’ and built the church at Otterbourne.

He was also a passionate supporter of education for all. He personally taught Charlotte Maths, Latin, and Greek and arranged tutors for modern languages. However, sadly, he believed that women should not be allowed to move out into the world. She thus became constrained to home early in her life, with occasional visits to cousins in Devon and a single visit to France, though later she travelled more freely, especially to London, but also on one occasion to Ireland.

From the age of seven she taught in the local Sunday School, a practice she kept up until she died in 1901.

Her earliest story, The Château de Melville, written in French was printed when she was 15 and sold to raise funds for the village school (though surely few locals could understand it). Significantly, only a few years earlier, the celebrated Oxford cleric John Keble (1792-1866) had taken up the country living of Hursley, which then included Otterbourne.

Today his legacy are the candles, the vestments, stained glass and art in general that are now taken for granted in Anglican churches. Some advocates of the trend, including Newman and Manning, converted to Catholicism, which for Keble was a move too far. The Monthly Packet was founded in 1851 with Charlotte Yonge as editor and continued until 1899. Described as ‘one of the first teenage magazines’, it lasted until 1899. It was published by members of the Oxford Movement, largely to counter extreme anglo-catholicism.

He quickly discovered her talents and set in her young mind the idea of writing fiction to embody Christian beliefs. He edited and revised her drafts and, more to the point, censored them – for example, no mention of drunkenness or insanity was allowed (though after his death she did touch on such social issues). So, from the very start Charlotte was put in a literary straight jacket. Moreover, when her torrent of work started to be published in 1844, at the age of 21, a family conference made clear that it would be wrong to write for money unless it was ‘devoted to the support of some good object’.

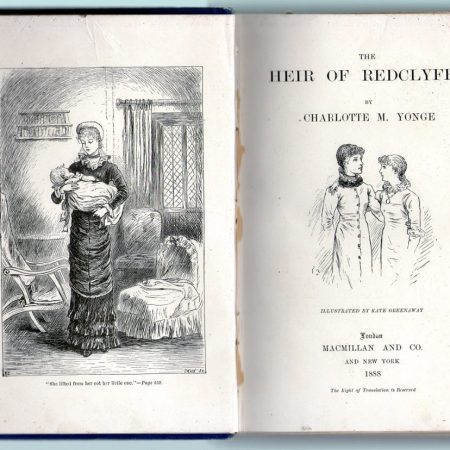

Her bestseller was The Heir of Radclyffe, published in 1853. It’s a simple romance in which Sir Guy Morville, the heir in question, falls in love with his guardian’s daughter, Amy. However, his cousin Philip, suspects him of gambling his money away, whereas he is paying off the debts of a dodgy uncle and he is banished. Later in the plot his philanthropy is proven, only for him to die nursing Philip.

Secretary of the Charlotte Yonge Fellowship, Alys Blakeway comments: ‘After reading her books one does come away with some idea of what the feminists were up against, though her ideas changed and became more liberal as she grew older. The whole point of the Heir of Redclyffe, was that Guy returns good for evil by nursing Philip in Italy and curing him of his unspecified fever, only to catch the fever himself and die, thus laying down his life for his cousin. The Victorians would not have missed the unwritten parallel with Christ.

‘Her biographers do tend to overestimate the influence which Keble and her father had on her life and work – after all, the former died in 1866 and the latter in 1854, and she went on writing till 1901. In her later books drunkenness and learning disabilities (though not insanity as such) do feature.

‘She was not a great traveller, but in later life she was free to go where she wanted when she wanted, particularly after her mother’s death in 1868. She went up to London quite often, and travelled about England visiting her friends, not to mention her trip all the way to Ireland!’

The Heir is in places a page-turner, but it is easy to understand why it is little read. Just look at Dickens’ Hard Times, published in the following year and full of hard-hitting social comment, or compare its first page with that of Pride and Prejudice, with its carefully crafted grabber: ‘It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.’

Modern audiences may not read Charlotte Yonge’s work for its literary qualities, but rather for its depiction of the foes that feminists had to confront. Moreover, since so many people bought and enjoyed her books – perhaps like those of a high-minded Georgette Heyer – they are a valuable source for understanding the Victorian mindset.